- What is the Description of Raga Malkauns and its Musical Characteristics?

- What is the Thaat of Raag Malkauns?

- What is the Speciality of Raag Malkauns?

- Swara Notations

- Malkauns Raag Bandish for Practice

- Famous Bandish (compositions) in Malkauns

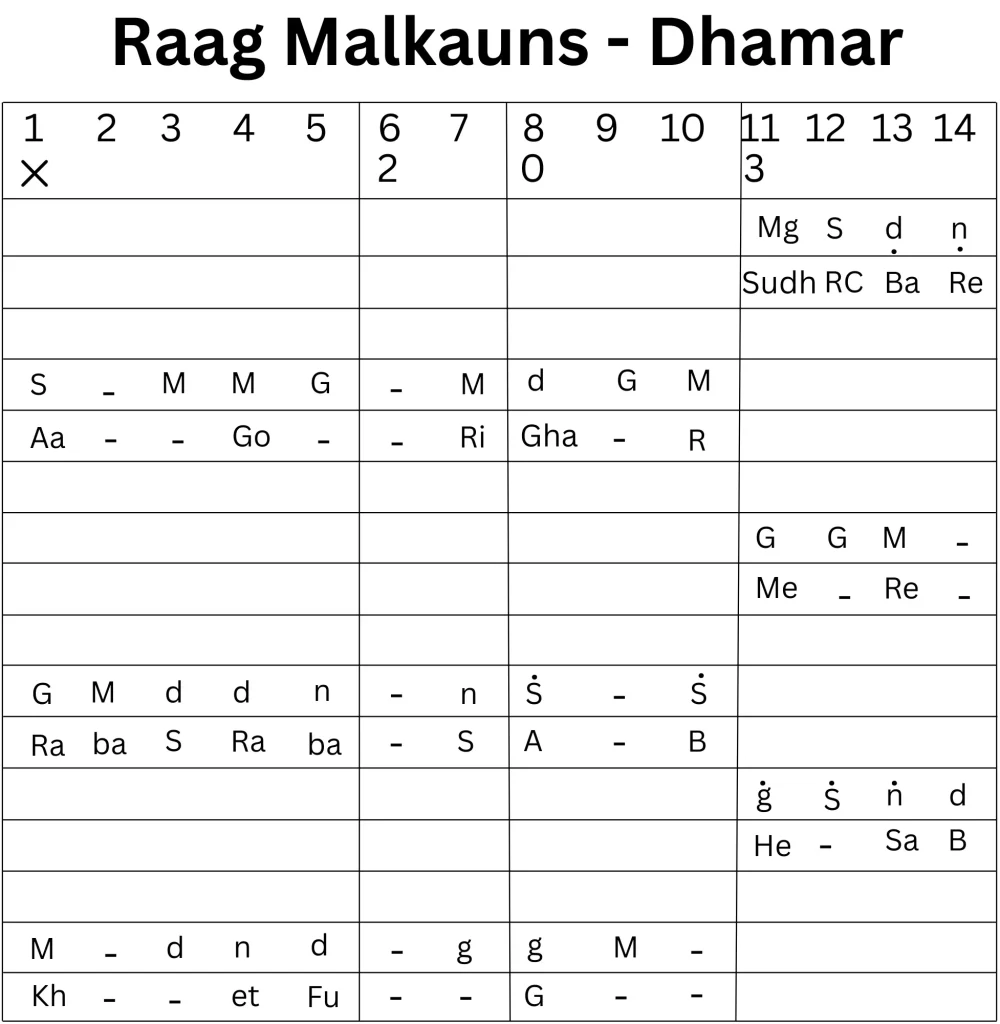

- What is the Notation of Dhamar in Raag Malkauns?

- Etymology of Malkauns Raag

- Art of the past : Raag Malkauns Miniature

- Traits of the Raag Malkauns

- What is the Mood of Raga Malkauns?

- What is the Effect of Raag Malkauns?

- Who Invented Raag Malkauns?

- Legendary performance & Bollywood Raag Malkauns Songs

- FAQs

Malkauns Raag, also known as Raga Malkosh, is an ancient raag and a very important one in both Hindustani and Carnatic Classical Music. In Carnatic Classical, it is known as Hindolam, not to be confused with the Hindustani Hindol. The name Malkaush is derived from the combination of Mal and Kaushik, which means he who wears serpents like garlands – Lord Shiva. In this blog we will look into Raag malkauns notes, songs and Raag malkauns bandish and other aspects of this Raag in detail.

What is the Description of Raga Malkauns and its Musical Characteristics?

However, the Malav-Kaushik mentioned in classical texts does not appear to be the same as the Malkauns performed today. Raag Malkauns has a long history and it appears to have undergone numerous changes over the centuries. The Raag is believed to have been created by Goddess Parvati to calm Lord Shiva, when he was outraged and refused to calm down after Tandav in rage of Sati’s sacrifice In Jainism

it is also stated that Raag Malkauns is used by the Tirthankaras [saviour and spiritual teacher of Dharma (righteous path)] with the Ardhamagadhi Language (a Prakrit language of North India) when they are giving Deshna (lectures) in the Samavasarana (divine preaching hall). Raag Malkauns belongs to the Kauns family which includes Chandrakauns, Sampoorna Malkauns, Sarang Kauns, Gunji-Kauns, Neel Kauns, etc. For more in-depth Raag Malkauns details one can explore, Its historical development, changes, and significance.

What is the Thaat of Raag Malkauns?

Raag Malkauns belongs to Bhairavi Thaat or scale of Hindustani classical music. It is a pentatonic (Audav-Audav) raga that has five notes that are Shadaj, Komal Gandhar, Shuddha Madhyam, Komal Dhaivat and Komal Nishad. In western classical notation, Raag malkauns notes can be denoted as: tonic, minor third, perfect fourth, minor sixth and minor seventh.

Did You Know?

Malkauns raag thaat, Bhairavi is known to be ‘the queen of raags sung in morning’.

One would think that with so many komal (flat) notes that it would have a strong minor quality about it. However, upon close examination one would be able to see that the absence of the pancham and the strong presence of madhyam causes the mind to “invert” it. Therefore, it tends to sound surprisingly similar to “Dhani” to which it has a murchana relationship.

In this Raag, Rishabh and Pancham are varjya ,that is, they are completely omitted. And raag malkauns vadi samvadi are Madhyam and Shadaj respectively. These Raag malkauns notes in combination portray darkness and secret. The stream of notes in this melody immediately produces the severely tranquil atmosphere. It is a serious and meditative raag, perhaps even sad. Therefore, it tends to be played at slow to medium tempo (vilambit laya to madhya laya) and rendered mostly in lower octave (mandra saptak).

What is the Speciality of Raag Malkauns?

Ornaments such as meend, gamak and andolan are used rather than “lighter” ornaments such as murki and khatka. Komal nishad in Malkauns raag aaroh avroh, is generally considered the starting note (graha swara), and the notes komal gandhar and komal dhaivat are performed with vibrato (andolit). The komal nishad in malkauns is different from the komal nishad in Bhimpalasi.

According to Indian Classical Vocalist Pandit Jasraj, Malkauns raag is “sung during small hours of the morning, just after midnight”. So, the best time to sing raag malkauns is late at night. The effect of the raag is soothing and intoxicating.

Swara Notations

Raag Malkauns, an associate of the Bhairavi thaat, has a pentatonic scale with the notes Sa, komal Ga (minor third), shuddh Ma (perfect fourth), komal Dha (minor sixth), and komal Ni (minor seventh), without Rishabh (Re) or Pancham (Pa).

| Swaras | Rishabh and Pancham Varjya; Gandhar, Dhaivat and Nishad Komal; Rest all Shuddha Swaras |

| Jati | Audav-Audav |

| Thaat | Bhairavi |

| Vadi / Samvaadi | Madhyam / Shadaj |

| Ideal time to sing raag malkauns | 3rd Prahar of the Night |

| Vishranti Sthan | Sa Ga Ma – Ma Ga Sa |

| Aaroh | Ni Sa, Ga Ma, Dha, Ni Sa’ |

| Avroh | Sa’ Ni Dha, Ma, Ga Ma Ga Sa |

| Pakad | Ma Ga, Ma Dha Ni Dha, Ma, Ga, Sa |

Malkauns Raag Bandish for Practice

*NOTE*

A dot before Ni and Dha denotes Mandra Saptak or Lower Octave.

Ga, Dha and Ni denote Komal Gandhar, Komal Dhaivat and Komal Nishad.

Sargam Geet

The above video includes Chalan of the Raag (Aaroh, Avroh and Pakad), followed by a sargam geet sung in teen taal madhya laya, the lyrics of which are as follows:

STHAYI

Sa’ Ni

Dha Ni Dha Ma Ga Sa Dha Ni Sa Ma Ga Ma Ga -2

Ma Ga Ma Dha Ni Sa’ Ni Dha Sa’ Ni Dha Ni Dha Ma, Sa’ Ni

ANTARA

Ma Ga Ma Dha Ni Sa’ – Sa’ Dha Ni Sa’ – Ga’ Ma’ Ga’ Sa’ -2

Ma’ Ga’ Sa’ Ga’ Sa’ Ni Dha Dha Sa’ Ni Dha Ni Dha Ma, Sa’ Ni

Bandish 1 : Piya Sang Lar Pachtani Mai

This Raag Malkauns’ bandish is sung in Teen Taal Madhya Laya and it starts from Khali.

STHAYI

Piya Sang Lar Pachtaani Mai -2

Piya Sang Lar Pachtaani

Dekho Aisi Madki Aini Mai -2

ANTARA

Un Bin Maika Kalna Parat Hai -2

Yuhi Rain Bihaani -2

Taraf Taraf Mai Rahi Sej Par -2

Jaise Meen Bin Paani , Mai

TAAN

STHAYI

1. .Ni Sa Ga Ma Ga Sa Ni Sa Ga Ma Dha Ma Ga Ma Ga Sa (8 Matra)

2. .Ni Sa Ga Ma Dha Ni Sa’ Ni Dha Ni Dha Ma Ga Ma Ga Sa (8 Matra)

3. Sa’ Ni Dha Ni Sa’ Ga’ Ma’ Ga’ Sa’ Ni Dha Ma Ga Ma Ga Sa (8 Matra)

4. Sa’ Sa’ Ni Dha Ni Ni Dha Ma Dha Dha Ma Ga Ma Ma Ga Ga (12 Matra)

.Ni Sa’ Ga Ma Dha Ni Sa’-

ANTARA

1. Sa’ Ni Dha Ma Ga Ma Ga Sa .Ni Sa Ga Ma Dha Ni Sa’- (8 Matra)

2. Sa’ Ni Dha Ni Sa’ Ga’ Ma’ Ga’ Sa’ Ni Dha Ma Dha Ni Sa’- (8 Matra)

3. Sa’ Ni Dha Ni Dha Sa’ Ni Dha Sa’ Ni Dha Sa’ Ni Dha Ma-

Ga Ma Dha Ni Sa’ Ni Dha Ma Ga Ma Dha Ma Ga Ma Ga

Sa Dha Ma Ga Ma Ga Sa (16 Matra)

Bandish 3 : Koyaliya Bole Ambuva Ki Daar Par

Raag Malkauns bandish ‘Koyaliya Bole Ambuva Ki Daar Par’ is sung in Teen Taal Madhya Laya and starts from Khali.

STHAYI

Koyaliya Bole Ambuva Ki Daar Par -2

Ritu Basant Ko Det Sandesva -2

ANTARA

Nav Kaliyan Par Goonjat Bhavra -2

Unke Sang Karat Rang Raliya

Ritu Basant Ko Det Sandesva

Bandish 4 : Mag Rokat Aiso Dheet Langar Va

Here is another Raag malkauns bandish ‘Mag Rokat Aiso Dheet Langar Va’. This Bandish is sung in Teen Taal Madhya Laya and starts from the 7th Matra same as in the Sargam Geet above.

STHAYI

Mag Rokat Aiso Dheet Langarva -2

Moso Karat Raar Lagaave Garva -2

ANTARA

Raah Baat Mag Rokat Tokat -2

Aiso Dheetha Nand Ke Chayalva

Famous Bandish (compositions) in Malkauns

| Bandish | Type | Taal | Style | Key Features |

| Aaj More Ghar Aaye Balma | Dhrupad | Chautal (12 beats) | Traditional | A devotional composition with a slow, meditative tempo. |

| Jago Brijraj Kumar | Dhrupad | Chautal (12 beats) | Traditional | A morning raga bandish, often sung in a devotional context. |

| Piya Ki Najariya | Khayal | Teental (16 beats) | Traditional | A romantic composition, often sung in vilambit (slow tempo). |

| Sundar Ang Daro | Khayal | Teental (16 beats) | Traditional | A bandish that highlights the beauty of the raga’s structure and mood. |

| Rang Piya Ko | Khayal | Teental (16 beats) | Traditional | A popular bandish, often performed in drut (fast tempo) to showcase virtuosity. |

What is the Notation of Dhamar in Raag Malkauns?

Etymology of Malkauns Raag

Famously auspicious, Hindu legend tells that the Raag was composed to soothe the rage of Lord Shiva, the God of destruction. Born into royalty, the princess Sati had renounced the material world in honour of Shiva, who she soon married. This displeased her father, the King, who insulted her and berated Shiva’s character.

Sati eventually consumed her anger, taking on the form of the Supreme Goddess Adi Parashakti. Storms broke, and her mortal body burst into flames, unable to contain the power of Goddess. Shiva was distraught when he learned of his wife’s death. He flew into wild rage, placing Sati’s charred corpse on his shoulders and throwing two locks of his hair to the ground. They sprung up to form the two Manibhadra, many armed warrior spirits who wielded swords, tridents and cleavers in their quest for vengeance.

Shiva became lost in an unending tandav dance of destruction and the band roamed the globe, decapitating the King and slaughtering his entourage.Shiva’s fury disturbed his fellow Gods, who implores Lord Vishnu, the preserver, to help. Vishnu brought Sati’s spirit back to earth, reincarnating her as Parvati, the Goddess of devotion. Parvati sought out Shiva, purifying herself by meditating naked in the harsh outdoors and eventually finding him in the forest.

It is said that Parvati first sung the raag as they wandered in the mountains, naming it Mal-Kaushik (he who wears serpents like garlands) after a prominent depiction of Shiva. The music calmed his mind, succeeding where all else had failed. Soon after the couple became husband and wife, Shiva took mercy on his vanquished foes, resurrecting those who had been slain and even reinstating the King to his throne (although he replaced his severed head with that of a goat).

Historians theorise that the raag may have been named through some possible combination of Malavas, an ancient Punjabi tribe, and kaisiki, a microtonal variant of Nishad (the 7th scale degree). But either way, Malkauns is inseparable from its darkly mythic reputation.

Many musicians still fear its supernatural powers. Some believe it can attract evil spirits if not handled correctly, as if the shadows of Shiva’s tandav dance are buried within the raag, waiting to escape. It is said that if one is not in a serious mood, then one should not play or sing Raag Malkauns, extra care must be taken with this raga.

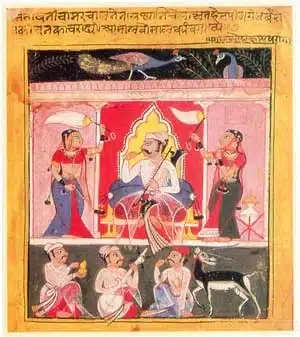

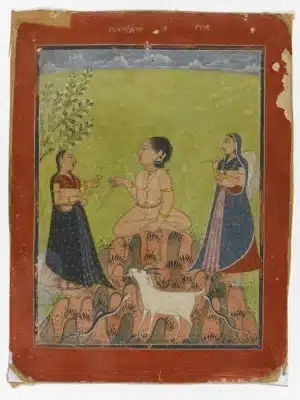

Art of the past : Raag Malkauns Miniature

The painting is part of a ragamala (garland of ragas), a series of miniature paintings that visually depict a raag, accompanied by a poetic inscription which invokes its mood, thereby bringing art, music and poetry together. It uses a reverse perspective, where objects that are further away are bigger and the vanishing point—where converging lines in a work meet—lies where the viewer is, not inside the painting. This has the welcome effect of making us participants in the unfolding scene.

On closer inspection, the colours dazzle, especially the luminous Indian yellow—believed to have been made with the urine of cows fed on mango leaves. The detail in the limited space is astonishing, from the short patterned lines that form the tree leaves to the rich floral pattern on sarees.

Similar ambiguities are found in other Malkauns’ classical Ragamala paintings, mediaeval artworks which depict ragas as characters, colours and shapes. Art historian Klaus Ebeling describes Raag Malkauns as “generally the most difficult to identify among all the ragas”. It can take many forms- a meditating yogi, a passionate lover, a nobleman intoxicating himself with betel nut, and a warrior-king holding a severed head while listening to distant music. These disparate figures may at first glance seem to have little in common, but they all share an immediate contact with some other realm, bridging two worlds with a charged stillness.

Traits of the Raag Malkauns

What is the Mood of Raga Malkauns?

Malkauns is a deceptive raag, balancing structural simplicity with unfamiliar tension. Traditionally, it is associated with Veer Rasa (the essence of courage), a quality imbued with acceptance, determination and the absence of infatuation. Traditions in Indian Classical Music ascribes Veer Rasa as not Veer Rasa of the battlefield but a sense of conquering the self and reaching a state of inner satisfaction. If there is heroism here then it is that of the post-battlefield return to camp, filled with relief, longing and mourning. Understanding the emotional effect and nuances of Malkauns is crucial for anyone dig deeper into Raag Malkauns details.

What is the Effect of Raag Malkauns?

Musicians describe Malkauns solemnly, as if they must sacrifice part of themselves to fully learn it. The gods of its origin myth were renowned for their severe feats of self-discipline, renouncing civilization and withdrawing to nature. So to some, the raag is a call towards ascetic isolation. But to others, the mythic signifiers point the other way. After all, Parvati used it to ground Shiva’s mind, helping him to re-engage with reality rather than to continue running from his grief.

Raag Malkauns in therapy shows that various laya (tempos) of Malkauns raag’ notes have different effects on high blood pressure and aid to raise low blood pressure. In Indian Culture, Malkauns affects the Nabhi or Manipura Chakra and is often said to evoke a state of intense tranquillity.

The Nabhi Chakra is situated behind the navel and it is said that when consciousness has reached the Manipura Chakra, we have overcome the negative aspects of Svadhishthana Chakra (located right below Manipura Chakra). There are many virtues of the Manipura Chakra such as knowledge, clarity, self-confidence, bliss and wisdom. The Manipura Chakra greatly supports good health and assists us in overcoming many illnesses. When the energy of this Chakra flows freely, the effect is like that of a power station supplying strength, vitality and balance.

Who Invented Raag Malkauns?

This raag is an ancient, traditional raag. It cannot be associated with a single specific inventor. However, it has been a part of Hindustani Classical Music system and is evolving over the past years. In Raag Malkauns, all five swaras are used to start and end melodies on so evoking a tense balance that swings you in many directions all at the same time, a balancing act between all points of the scale like a quantum observer watching from a distance while the universe unfolds. Though this raga has comparatively few rules it is still regarded as one of the hardest to master.

Legendary performance & Bollywood Raag Malkauns Songs

Malkauns Raag songs have a particular pull for musical obsessives. After all, many have become lost in it. Khayal vocal greats such as Pandit Bhimsen Joshi and Ustad Amir Khan often replaced it at the centre of their repertoire, and Kirana gharana exponent Pandit Pran Nath spent a lifetime working on it. He retreated to live in mountain caves for years at a time, singing to the birds and drawing inspiration from the sounds of water. His ascetic routines even resemble the tales of Shiva and Parvati in the forest.

It is sometimes said to be most at home when sung rather than played. But instrumentalists have made it their own too – Pandit Nikhil Bnaerjee’s Sitar, Ustad Amjad Ali Khan’s sliding Sarod, Ustad Sultan Khan’s bowed sarangi, Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia’s flute to name a few. Sangeeta Shankar’s violin brings a warmer approach, a little reminiscent of Hindolam, the carnatic equivalent.

It retains its distinctive essence even in non-classical settings. Mohammed Rafi’s famous rendition of Man Tarpat Hari Darshan Ko places it in a filmy context, as does Asha Bhosle’s Rang Raliyan. Mentioning a few more bollywood songs based on Raag Malkauns:

1. Ye Toh Sach Hai Ki Bhagwan Hai from the movie “Hum Saath Saath Hain”.

2. Tu Chhupi Hai Kahan by Manna Dey and Asha Bhosle.

3. Balma Mane Na by Lata Mangeshkar.

4. Jaan E Bahar Husn Tera Bemisal Hai from the movie “Pyar Kiya Toh Darna Kiya”

In 1968, Shankar-Jaishankar featured it on their landmark Raag Jazz Style, writing a melody that would be picked up by Sarathy Korwar’s Upaj Collective a half-century later in London. Don Cherry’s intriguing free jazz rendition wanders further from the original mood.

Whatever the setting, Raag Malkauns notes draws the listener away from impulse and delusion towards a suspended realm of contemplation. It balances tranquillity with severity, calming Shiva’s dance of destruction and turning him to reflect on the suffering he had caused. It is unique in its ambiguities, and continues to captivate modern listeners.

No amount of writing can describe this raag in a true sense. Listen to it to experience the bliss of malkauns. Frankly the journey on which malkauns takes the listener to would be an experience to cherish.

More Malkauns Raag Songs for Better Understanding

Rang Raliyan

Rang Raliyan is a soulful song based on the elements of Malkauns raag. The lyrical depiction of the emotions, love and longing, so beautifully intertwined with Malkauns raag notes captivates its listeners.

Aaye Sur Ke Panchhi Aaye

‘Aaye Sur Ke Panchhi Aaye’ is one of the raag Malkauns songs featured in the film ‘Sur Sangam ‘. This timeless piece classical traditions and poetry resonating reflective moods. It is performed by Rajan Mishra and Sajan Mishra.

Man Tarpat Hari Darshan Ko Aaj

Outstanding rendition by Mohammed Rafi with raag Malkauns parichay, throughout the song makes ‘Man Tarpat Hari Darshan Ko Aaj’ resonate well with the listeners. Now, who wouldn’t love charming poetry in the sounds of Malkauns raag aaroh avroh!

Om Namah Shivay’ Raag Malkauns

Om Namah Shivay is one of the popular and cherished raag Malkauns songs. It is a devotional rendition powerfully capturing the essence of Lord Shiva. Its intense and somber moods amplifies the sense of devotion as well the reflective mood of the raag remaining top in raag Malkauns songs list.

Aaj More Ghar Aaye Baalma

A beautiful Raag malkauns bandish expressing the joy and anticipation. This song is rich in traditional roots featuring lively and melodic accompaniments. Many classical artists have performed this timeless piece highlighting themes of love, happiness expressed by raag Malkauns parichay in the melody.

Closing Thoughts!

No amount of writing can describe this raag in a true sense. Listen to it to experience the bliss of Malkauns. Frankly the journey on which Malkauns raag notes takes the listener to would be an experience to cherish. Book a free demo with musicmaster today to learn more.

FAQs

Which raag is most difficult?

Difficulty if any raag can be subjective. It depends on the complexity of its structure and characteristics.

How old are Raag Malkauns?

It can be over a 1000 years old.

What are the notes in Raag Malkauns?

Sa, Ga, Ma, Dha, Ni, Sa are the notes in Raad Malkauns.

What is the mood of Raag Malkauns?

Raag Malkauns is associated with Veer Rasa and moods such as relief, longing and mourning.

How does Raag Malkauns differ from Raag Bhairavi?

Both the raags are not similar and differ in the swaras used in it, its structure and mood.

Who are the famous exponents of Malkauns?

Bade Gulam Ali Khan, Kesarbhai, Omkarnath Thakur are some of the famous exponents of Malkauns.

Is Malkauns good for meditation?

Yes, Malkauns is, indeed, good for meditation.

What is the story behind Raag Malkauns?

Raag Malkauns is believed to be created by Goddess Parvati, to calm down Lord Shiva during his Thandavam.

Why is Raag Malkauns played at night?

Raag Malkauns is played at night because of its contemplative and slightly somber nature.

Related blog: Raag Bhimpalasi